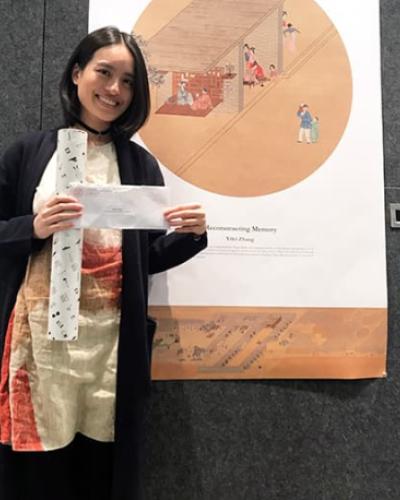

My senior thesis project is a memorial for the centuries-old, but now much-diminished, Jewish community of Kaifeng, in China’s Henan province. When I started researching Jewish architecture for my thesis design, I realized that it would be hard to find precedents that I could use as models. Historic Jewish buildings or synagogues in other countries bore little if any resemblance to the former synagogue of Kaifeng. Also, unlike their counterparts in the West, the Kaifeng Jews do not have a history of collective trauma. They needed a different approach than most contemporary Jewish memorial designs. Still, like memorials in other countries, my proposed commemorative architecture for the Jews in Kaifeng aims to mediate between the present and the absent, the living and the dead, the memory and the memorial.

Since my design was to serve not only as a memorial for the lost Jewish culture, but also help the current community reclaim their Jewish memory, I sensed it would be superficial and arbitrary to start my project with a formal design. What was most urgently needed would not be a physical form or building, but a space that allowed people to rediscover their identity. Therefore, I started my design with research on the Chinese Jewish identity.

The only information about Chinese Jewish space I could find was a perspective drawing of the Kaifeng synagogue by the Jesuit missionary Jean Domenge in 1722. Based on this drawing, I recreated the plan of the original synagogue complex. It seemed like a typical traditional Chinese building complex with Chinese construction methods and materials. However, comparing its plan with the plans of other local formal building complexes, I found that the boundary wall was very important to the Kaifeng synagogue. To verify this finding, I continued my research about the boundary wall in Judaism and local Chinese culture, where the wall plays a vital role. Most of the local dwellings were built in Hutong style with courtyard houses. The only place allowing activities to take place was the space beside the wall in the narrow alley.

I moved on to learn more about Chinese Jewish identity. In Kimberly Cheng’s 2013 Cornell B.A. thesis “The ‘Lost’ Jews of China,” she argues that instead of considering the Kaifeng Chinese Jews as passively assimilated by the Chinese culture, we should understand the Kaifeng Jews as actively absorbing the Chinese culture into theirs and forming a new identity. She further argues that this process helped the Kaifeng Jews to keep their Jewish identity for 1,000 years. Consistent with Chinese Confucianism, Kaifeng’s Jews valued family above all. As long as the family was sustained, they would never lose their Jewish identity.

My thesis proposed a pavilion that would allow the Kaifeng Jews’ cultural and religious practices to take place, while also commemorating the absent community. Echoing the original synagogue’s plan, the pavilion I designed includes different spaces, secular and religious, some loosely defined and some intended for more specific uses. These spaces are divided by five thresholds constituted by walls built with local materials. Each wall contains a builtin structure that could be converted to benches and tables. Thus, every threshold or group of walls and the spaces between thresholds can facilitate different activities. For example, the first group of walls could function as a Lantern Festival market; the second group of walls provided space for communal eating during festivals. Besides the wall structure, there are three courtyards between each threshold. The first courtyard, an open space, would allow the descendants of Kaifeng Jews to build Sukkot for the fall holiday. On the right of the second courtyard, a communal kitchen facilitates festival cooking. The third courtyard includes a performing space and event space on the right, and an exhibition hall at the end.

Commemoration is marked by features embedded in the pavilion that mourn the lost Jewish history. When the rooms are not occupied for festival celebrations, they become marks of absence. The roof of each room has an opening that signals the absence of the original buildings in the synagogue complex. The absence of the Jewish community is also represented by the light and the construction material. The Kaifeng synagogue was destroyed by a devastating flood on June 16, 1841. The “death” of the synagogue is marked in my design by the use of different materials on the wall and ground. While the main construction material was brick, similar to most of the local vernacular architecture, stones imbedded on the brick walls and ground mark the light coming through the skylight on that sad June 16th.